Hi folks,

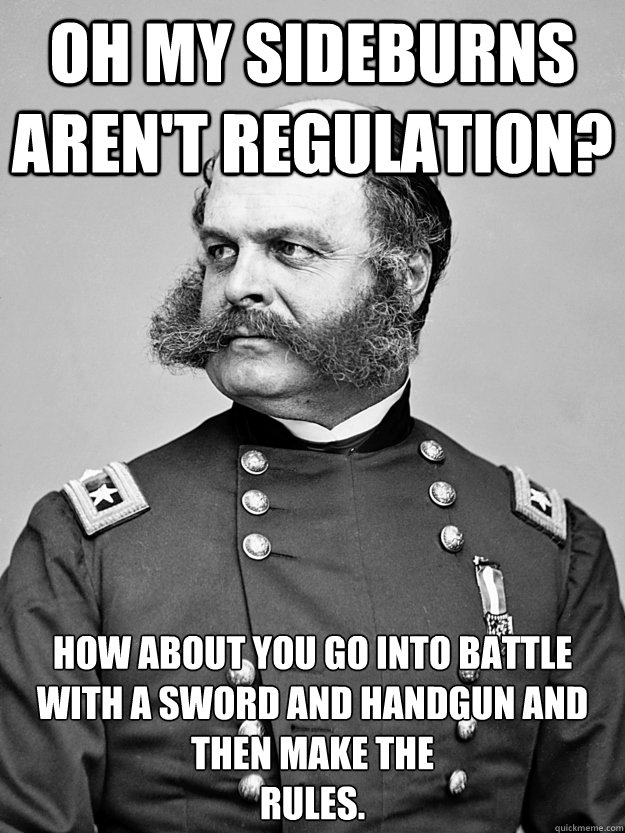

I have a (totally unbiased) fondness for historical figures with sweet sideburns, so it’s not shocking that I like Theodore Parker. I mean, he’s no Burnsides, but who is?

So Theodore Parker – who is he? He was a Unitarian minister in antebellum New England. Abolitionist, transcendentalist, and pretty big brain – he generated a lot of good quotes in his day. Among them:

I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.

Pretty solid, right? In just a few short sentences, he divines the future evolution of humanity, prepares the reader for a long journey, and admits his inability to see the destination himself. It would be totally understandable for any subsequent orator to simply reference Parker’s quote rather than try to improve or build upon it. But those who want to affect change don’t usually make do with the status quo. So, in February of 1965 – in the shadows of the assassinations of JFK and Malcom X – Martin Luther King Jr delivered a sermon at the Temple Israel of Hollywood. In it, he included the following quote:

the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice

It’s a quote that King used many times, including during the March on Selma in 1965. King, for all his awe-inspiring oratory skills, wasn’t afraid to lean on those who came before him and improve upon what they produced. The same is true for all of our great leaders – they make use of the works of others and they don’t hold those works sacrosanct. They update/change/edit in order to improve those works for their needs. Parker’s quote worked well for a more verbose era, but King needed something more succinct – so he made some improvements.

The same is true for all of us. What we do may not hold a candle to the works of Parker, King, and other giants of history, but our work is important nonetheless – important enough to warrant critical examination of those who came before us and important enough for us to make improvements as needed. NIST special publications, OMB memorandums, FISMA, and other guiding documents for our field have been created by smart, dedicated, driven people – but they’re not infallible and they’re not custom tailored for our specific needs.

It’s incumbent upon us to lead in our own way and, in the pursuit of a better tomorrow, bravely make changes to that which may seem “good enough”. It’s not dismissive or disrespectful – it’s just improvement and it should be welcomed.

Rex